François de Callières

From Marteau

|

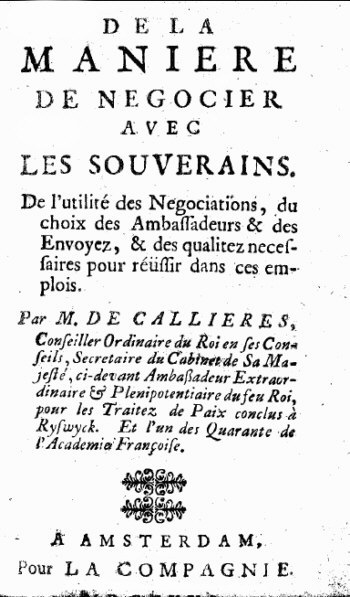

François de Callières, sieur de Rochelay et de Gigny, was born on May 11 1645 at Thorigny in Lower Normandy. He died on March 5, 1717, full of honors, in his Paris house, 16 rue Saint Augustin, its walls covered with Flemish, Dutch, and Italian masterworks, and its cabinets full of books, including a French edition of John Locke. Conventionally referred to as a diplomat and man of letters, de Callières would not have recognized himself in that description. The word diplomat is a coinage of the early 19th century, arguably an unfortunate one, and while de Callières published a total of eight books, and was a member of the Académie française, he certainly did not think of himself a member of the literary profession. There is no proper biography of de Callières. The memoirs which he left to his friend and executor the abbé Eusèbe Renaudot are not known to have survived. But the principal facts of his life are known. At the tender age of 22, de Callières is commissioned by the Longueville family to travel to Poland to secure the election of its scion, the young Comte de Saint Pol, to the Polish throne. The death of the gallant Count in a skirmish at a crossing of the Rhine in 1672 dashes the hopes of the would-be kingmaker, the first of many disappointments in a long public career. But the prolonged residence in Poland establishes a Polish connection. Between 1672 and his election to the Academie française in 1689, de Callières served in a confidential capacity at various European courts. In 1675, he was employed by Charles-Emmanuel II, Duke of Savoy in 1675 in an effort to establish an alliance with France, but the Duke's death ended this effort. In 1676, as the Savoyard envoy to the court of the Electress of Bavaria, he is commissioned by her to arrange the marriage of her daughter to the French dauphin. Her death brings an end to his role in the negotiations, which came to fruition in 1680. By 1688, we find de Callières back in Paris establishing a reputation as a writer and associated with the former Grand Treasurer of Poland, Mortsyn, head of the French party in Poland, who has escaped with a considerable part of the Polish treasury. De Callières negotiates a noble marriage for Mortsyn's son with a mademoiselle de Chevreuse. He also produces a volume on the relative merits of the ancients and the moderns which takes a judicious and sensible middle view. A panegyric of Louis XIV secures election to the Academie Francaise in 1689. A series of books on language and wit follow, written in a lively conversational style. In 1694, the Polish connection brings de Callières back into the world of international negotiations. After a particularly bad harvest, Louis is ready to explore a negotiated settlement with the League of Augsburg, and the Polish resident in Amsterdam, a merchant active in the grain trade, tells de Callières that the burgers of Amsterdam are ready for peace. De Callières conveys the message to Colbert the Croissy, the foreign minister, and the King gives his blessing. With a more senior figure, de Harlay, de Callières is sent in great secrecy to Flanders to make contact with the representatives of William III. His conduct of the negotiations is skillful, though not without its ups any downs, and three years later de Callières is one of the three plenipotentiaries who sign the Peace of Ryswick for France in 1697. On his return to France, in February of 1698, de Callières is rewarded with appointment as one of four private secretaries to the King, but not with the embassy he had hoped for. In 1700 on the death of Michel Rose he is named principal secretary ("plume"). The Duke de Saint Simon, who greatly admired de Callières, describes the post as one for master forger, involving the counterfeiting of the King's handwriting; a better analogy might be that of principal undersecretary in a modern foreign ministry. In the Saint-Simon's memoirs we see de Callières exploiting the Duke's innocence. He convinces Saint-Simon to present a proposal for a negotiated settlement with Spain which reflects de Callières' dovish views, but it is dismissed with an obscenity by the Duke de Beauvilliers. Saint-Simon says of de Callières that he had the courage to tell the truth to the King, and often brought the King and his ministers around to his view. This strength of character is borne out by the record of de Callières negotiations with the Dutch. It may also account for the fact that apart from a mission to the Duke of Lorraine, de Callières is not sent abroad again. On the death of the Sun King, de Callières publishes two books intended to be companion volumes. One is the best known manual for diplomats ever written, De la manière de négocier avec les souverains. Thomas Jefferson had a copy in his library at Monticello. Harold Nicholson, the British diplomatist, admired it greatly. De Callières advises honesty, discretion, loyalty, and putting oneself in the position of the other party. Sovereigns are advised not to send their least qualified courtiers to represent them abroad: better to keep them closer to home, where they can do less trouble. The other, De la science du monde et des connaissance utiles à la conduite de la vie..., contains much useful counsel to ministers of state with regard to the staffing of their offices and the conduct of the public business. It is quite forgotten. Unpublished letters written by de Callières during the period 1694-1670 to the Marquise d'Huxelles (BNF, manuscrits français, 24983) provide insight into de Callières' character. This loyal servant of Louis the Great praises the selfless devotion to the public good of the ancient Romans, of Titus, and Trajan, and the honesty and simplicity of the Dutch Republic. He criticizes arrogant conquerors who covet their neighbors territory. Better, he writes, a small flock, well-fed than a larger herd of famished sheep, and better to keep to the natural borders of France, including the Rhine "if we can go that far". All hierarchy is ultimately based on force. But we must live in the world as it is, not the world as we wish it were, and since we can't govern ourselves, how can we claim to reform others? Mme. d'Huxelles ran a sort of news bureau and salon where, according to one observer, "the statesmen of Europe come to learn of their fate". She watches his back, and when de Callières comes under attack at Versailles he writes two letters to seek support, one to her, and the other to the King. She had also been devoted in her youth to the Comte de Saint Pol, or so her friend Mme. de Sévigné tells us, and she attempts to arrange a match for de Callières with a member of her set, Mlle de Comminges, a lady of a certain age. He is interested, particularly as the lady shares his devotion to the public good, and he declares his feelings, but the lady eventually marries the first President of the Parlement of Bordeaux instead. Although a man of considerable property, thanks to royal favor, de Callières never marries. In one of his last letters to the Marquise, written in June of 1700 while on a mission to the Duke of Lorraine, he quotes the shepherd's lament from Guarini's "Il Pastor Fido" that returning Spring brings with it only the cruel memory of past loves. He leaves the bulk of his estate to the poor of Paris. |

Literature

- François de Callières, De la manière de négocier avec les souverains (Amsterdam: pour la Compagnie). gallica